This guest post is by Doug Hung, Director, Blanchard Taiwan.

This guest post is by Doug Hung, Director, Blanchard Taiwan.

Every year, China conducts a nationwide college entrance exam for all high school graduates. The exam spans two days and covers Chinese, foreign languages, mathematics, and a student’s choice from one of the humanities (politics, history, geography) or sciences (physics, chemistry, life sciences).

Students are also required to write an essay to demonstrate their critical thinking and analytical capabilities.

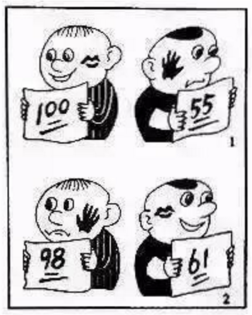

In 2016 the national exam board provided a pair of portraits as the essay prompt. Students were asked to write an 800-word essay based on the picture.

In the top example, a student is shown receiving a perfect score of 100 and a resulting kiss on the cheek from a pleased mother, while the other student receives a below 60 percent failing grade with a resulting mother’s slap to represent disapproval. In the bottom example, the passing student scores 98 percent but doesn’t meet his mother’s standards, while the other student barely passes and gets an approving kiss.

In the top example, a student is shown receiving a perfect score of 100 and a resulting kiss on the cheek from a pleased mother, while the other student receives a below 60 percent failing grade with a resulting mother’s slap to represent disapproval. In the bottom example, the passing student scores 98 percent but doesn’t meet his mother’s standards, while the other student barely passes and gets an approving kiss.

This essay prompt points to a truth that is often overlooked when measuring performance at work—the subjective nature of measurement.

Corporations set elaborate guidelines for performance reviews, designed to promote and enhance meritocracy. Yet in reality, all systems have flaws—and when they are carried out by individuals, who have inherent bias, performance evaluations can often overstate or understate an individual’s actual contribution within the organization.

Every organization has both stars and laggards. We tend to shower stars with praise and opportunities; yet, as stars take on more responsibility, the likelihood of them making mistakes gets higher. Is the organization prepared to reward them or to criticize their failures?

On the other hand, oftentimes little is expected of low performers, and organizations are known to direct a substantial amount of resources to manage them. When laggards demonstrate initiative or spurts of excellence, teams seize the moment and shower them with praise in hopes of continuing progress. If an organization and its stewards really hold performance standards equally across all types of performers, all performance results should be treated equally.

Whether one believes management resources are better spent strengthening stars or improving low performers is a matter of debate. The reality is that managers do—and should—inject subjectivity into their evaluations.

Whether one believes management resources are better spent strengthening stars or improving low performers is a matter of debate. The reality is that managers do—and should—inject subjectivity into their evaluations.

The key is to recognize that performance reviews should be clear in definition but flexible enough to acknowledge the nuances that come with human interaction. Failure to do so undermines faith in the objectivity of any performing benchmark.

We all use metrics to measure others and ourselves. As companies continue to examine their performance review processes, we should remember that all metrics are ultimately references of an individual’s contribution. Performance reviews must be used to encourage people to excel. This can be done only through an approach that is objective, constructive, and judgment free. ![]()

About the Author

More Content by David Witt